Chris Bigelow, with grandson Jack.

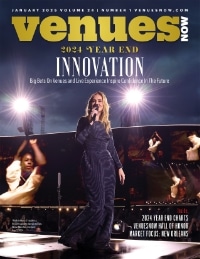

Chris Bigelow: ‘Know What I Mean?’

50-Year Food Service Vet Still Tells It How It is

Chris Bigelow picked a memorable day to launch his food service career in sports and entertainment. It was May 25, 1974, which happened to be Bigelow’s 21st birthday, and he was a trainee at Denver Coliseum for AraServ, forerunner to Aramark, which ran the concessions. Sly and the Family Stone headlined a concert that night at the arena and Sly was nowhere to be found.

It came as no surprise to those working the event, considering Sly Stone’s history of missed appearances, but still, the concessionaire preferred to avoid having a riotous crowd on its hands at the home of the National Western Stock Show, despite all the beer they would sell over the next several hours.

“They finally find Sly and he’s passed out in his hotel room,” Bigelow said. “They bring him in on a stretcher and prop him up. I was standing backstage, looking on, thinking how the hell is this guy going to do anything? This was at 2 a.m.

The building had as many delays as they could and the per caps were great because of all the breaks. The music came on and he started singing. The place goes bananas and it’s a hell of a concert.”

Bottom line, “you learn the concessions biz really quick as to what’s going to happen,” Bigelow said.

Fifty years later, Bigelow has taught countless others the lessons he learned about feeding sports fans, concertgoers and those attending family shows.

He’s a pioneer, carving a niche as one of the industry’s first food consultants. Now, there are a half-dozen individuals working in that space. Bigelow’s contributions to the industry have earned him inclusion into the 2024 VenuesNow Hall of Honor, this publication’s version of the lifetime achievement award.

Initially, Bigelow spent 15 years working for food vendors AraServ and the old Volume Services before starting his own firm, The Bigelow Companies, in 1988, to consult with teams and public assembly venues about the intricacies of food and drink and how to maximize revenue from a captive audience.

Apart from his full-time job, Bigelow has given back to the industry by serving as a teacher in a classroom setting for many years at the Venue Management School, run by the International Association of Venue Managers.

Antony Bonavita, executive vice president for Rock Entertainment Group and the Cleveland Cavaliers, runs Rocket Mortgage FieldHouse. Bonavita was among Bigelow’s students in 2001 when he worked at Stony Brook University, seven years before embarking on a career in the NBA.

Twenty-three years later, Bonavita still leans on Bigelow for guidance, hiring him to consult on hospitality spaces tied to the $3.5 billion mixed-use development along the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland, to be anchored by the NBA team’s new practice facility. Bonavita leads the project for Cavaliers owner Dan Gilbert, whose Bedrock Real Estate is the developer.

“Chris is going to come in and provide some last-minute support,” Bonavita said. “It doesn’t feel right for me when Chris is not on a project, because I have so much confidence and respect for him. Chris always gives it to me straight. What you see is what you get and that’s what I love most about him.”

Over time, Bigelow has been an asset for building managers, cities, sports authorities, consultants and young professionals coming out of school, said Susan Sieger, president and CEO of Crossroads Consulting, which provides feasibility studies, market research and funding strategies for arenas, stadiums and convention centers.

“Chris has been a mentor to me, because food was an area I didn’t focus on; I’m more on the economics side,” Sieger said. “He’s an icon in the industry and always has time to answer questions, no matter who’s asking. He’s also an amazing resource for restaurants in any city you go to in the U.S.”

FEARSOME FOURSOME: Chris Bigelow, from left, on the links with former IAVM president Jack Zimmer, Larry Perkins and Russ Simons.

……………………………………………………………….

Yep. “Know what I mean?”

It’s Bigelow’s catch phrase, and there aren’t many people he’s crossed paths with over the past half-century that haven’t heard it. Bigelow estimates he’s been involved in about 500 food deals since his first consulting gig in 1988 at Pilot Field, now Sahlen Field, the minor league ballpark in Buffalo, New York.

Bigelow’s acumen and honesty as an operator helped strengthen his consulting business. He gained the trust of his clients, cutting through the “smoke and mirrors to get to the elements that really matter,” said Matt Kenny, Arrowhead Stadium’s executive vice president of operations and events.

“Chris was the consultant through our newest RFP, which ended up being an 11-year deal through the end of our stadium lease,” said Kenny, employed by the Kansas City Chiefs. “We retained the incumbents, but without his support, we wouldn’t have had the number of bidders and the outcome we ended up with. We got a good deal, and both Levy and Aramark have been able to grow their business, and Chris deserves credit for a lot of that.”

Veteran sports executive Richard Andersen worked with Bigelow multiple times over his career, including Andersen’s stint as president of the San Diego Padres and general manager of Petco Park; Northlands, a multi-venue complex Andersen oversaw as president and CEO in Edmonton, Alberta; and a few years ago, Banc of California Stadium, now BMO Stadium, home of Major League Soccer’s LAFC, where Andersen spent one year as interim GM.

“Chris was always able to represent the client without compromising us to any particular service providers,” Andersen said. “The role he played can be challenging, but Chris was always about doing the right thing and I respect that.”

Know what I mean?

……………………………………………………………….

Bigelow grew up in suburban Philadelphia and attended Lower Merion High School, the same institution where Kobe Bryant made his mark before joining the NBA. Bigelow’s father ran a candy store in town, which explains his “bad sweet tooth” at age 71.

Early on, Bigelow enjoyed the hustle and bustle of retail outlets open 24 hours a day. In high school, he got a job working the front desk at a Howard Johnson’s motel in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania. He enjoyed it and decided to pursue a career in hospitality.

In the early 1970s, the two big colleges offering degrees in hotel and restaurant management were Cornell and Michigan State.

Bigelow got accepted to both schools, but he opted for Michigan State because Cornell had a formal dress code; plus, Bigelow’s father was from Detroit and had relatives in the region, which made it an easier decision, he said.

After one semester in East Lansing, Michigan, Bigelow thought maybe college wasn’t for him.

He got a job working at the old Playboy Club in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, a Midwest ski resort. It sounds glamorous, but that wasn’t the case.

Management sold ski packages to unsuspecting Chicagoans despite often having a lack of snow on the property, which made for irate patrons, he said.

Chris Bigelow in his younger days.

Bigelow lasted three weeks at the Playboy Club before deciding to return to college.

He landed at the University of Nevada-Las Vegas, where he heard the school had a growing hospitality management program in a city where wining and dining is the No. 1 industry. At UNLV, the average student age was 27. Many of them lived in Vegas and already worked at casinos, while others went back to school to get an education after returning from the Vietnam War.

“It was very different than a typical college experience,” Bigelow said.

Bigelow worked at a few more hotels over the summer months before graduating from UNLV and training with AraServ in Denver. From there, he went to Indianapolis in August 1974 for his first permanent position at Butler University, including historic Hinkle Fieldhouse.

One year later, Bigelow was transferred to his hometown, landing at the Spectrum, one of the busiest arenas in the country, with the Sixers and the Flyers and tons of boxing during Philly resident and heavyweight champ Joe Frazier’s heyday, he said. On weekends, he worked at a small racetrack in New Jersey.

“I was young and stupid, working seven days a week,” he said.

Bigelow landed in Kansas City in 1976 after Ken Young, his old roommate in Indy with Volume Services and a 2022 VN Hall of Honor recipient, convinced Bigelow to move back to the Midwest, where Young was stationed at Kemper Arena. Bigelow took over as GM at Royals Stadium, where he met his wife, Marcia, who was head cashier there.

The Kansas City Royals had great baseball teams in the late 1970s during Bigelow’s tenure at the ballpark, drawing big crowds and hungry fans. After losing to the hated New York Yankees in the ALCS from 1976-78, the Royals made the 1980 World Series, losing to the Phillies, Bigelow’s hometown team.

“I always say this, but nobody cared about that World Series, because the Royals had beat the Yankees and the town went nuts,” he said.

In the mid-1980s, Bigelow was promoted to regional VP, overseeing accounts across the Midwest, before turning to the sales side. At the time, Volume Services went through some ownership changes. Bigelow quit his job in 1988 after declining to move to Chicago, where the corporate office was situated.

“I decided to open a restaurant, as everybody that’s dumb enough in the food business wants to do,” he said. “Everyone asks me why it’s called The Bigelow Companies, plural. My clever idea at the beginning was to have a restaurant division and a consulting group. The restaurant thing never happened.”

……………………………………………………………….

KC STRONG: Chris Bigelow and his staff in Kansas City, Missouri in 2008, which at one point included seven designers of concessions spaces.

Bigelow kept in touch with his old colleagues. One day, former Volume Services executive Vince Pantuso, who was doing some consulting on his own, contacted Bigelow and asked him to help open new Pilot Field, the triple-A home of the Buffalo Bisons.

Bigelow spent the summer of ’88 in Buffalo. From there, the Pittsburgh Pirates, whose top affiliate played at Pilot Field, asked him to consult on the food operation with their double-A team in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

“I thought, maybe there’s something to this consulting thing,” he said.

After Bigelow attended the IAAM conference in Nashville to spread the word about his fledgling business, he consulted on the development of the Suncoast Dome, now Tropicana Field. At the time, the stadium didn’t have a primary tenant until the expansion Tampa Bay Rays began play in 1998.

In St. Petersburg, Florida, it was the first time Bigelow prepared a request for proposal. Things snowballed from there; teams kept calling him to review their plans and advise them on the food service aspect.

As his business evolved and a building boom took off in the late 1980s and through the 1990s, Bigelow expanded his reach to designing concession stands and kitchen spaces. At one time, he had seven designers on board. Some clients hired him to both issue RFPs and map equipment layouts.

“Having an operations background, I understood what the concessionaires needed,” Bigelow said. “In the old days, nobody thought about food and beverage, gave them enough space with exhaust to cook and enough freight elevators to move product around.”

That all changed after team owners started paying attention to fan surveys and recognized the importance of food and drink to the overall experience.

Bigelow remembers that Dick Jacobs of the Cleveland Indians, now the Guardians, was the first team owner to attend Bigelow’s design meetings for the MLB club’s new ballpark that opened in 1994. The stadium was Levy’s first contract for premium dining outside of Chicago, its home base.

“Food and drink finally got a seat at the adults table during design to drive revenue, but fan amenities also became important,” Bigelow said.

After the pandemic, Bigelow stripped his business down, getting out of the design side to focus on RFPs and negotiating food deals, much like his early days as a consultant. These days, he’s doing more college work than the pros, a reflection of schools upgrading their facilities and getting into the alcohol business, where they want to make sure they do it right, he said.

Bigelow, who has homes in Kansas City and Naples, Florida, said he plans to retire for good by the end of 2025. He’s been wanting to take a cruise around the world with Marcia. At his wife’s request, he cut it down to a three-month trip in 2026 from his original plan to spend 150 days on the high seas.

“I’m winding things down, no question, unless the phone rings,” he said. “Know what I mean?”