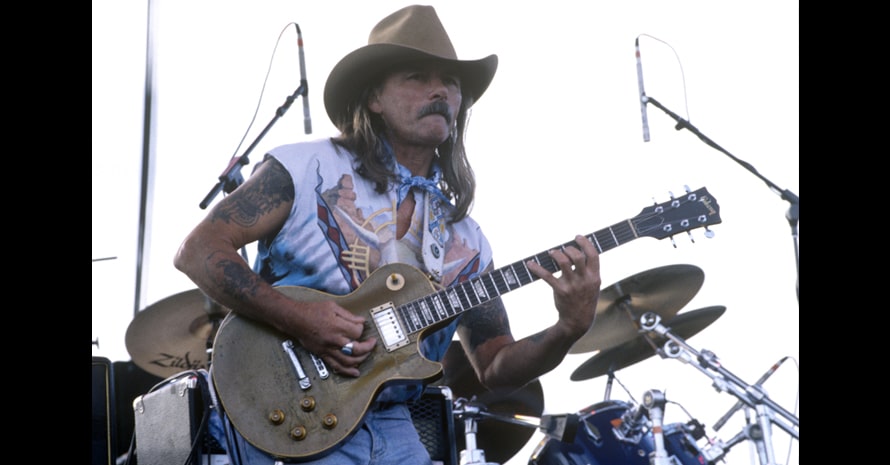

BROTHERLY LOVE: Dickey Betts leads the Allman Brothers Band during a 1993 show at Laguna Seca Racetrack in Monterey, California. (Getty Images)

Betts influenced many southern rock guitarists

Dickey Betts was the secret weapon for the Allman Brothers Band, “pickin’ on that red guitar” in the shadow of Duane Allman before taking a leadership role after Allman’s tragic death in a 1971 motorcycle accident, two years after the group was formed.

Thirty years later, Betts, famously name-dropped in that 1974 Charlie Daniels tune,”The South’s Gonna Do It Again,” departed from the Allman Brothers, the originator of the southern rock sound. It was a messy divorce that left Betts estranged from his bandmates. He spent the next 18 years touring with his solo outfits, Great Southern and the Dickey Betts Band, before his retirement in 2018.

Betts died on April 18 of cancer at the age of 80 at his home in Osprey, Florida. His legacy is a complicated one, like many musicians. Bottom line, Betts played a critical role for reinventing the Allman Brothers on multiple occasions, which would spend 45 years on the road and survive multiple breakups, according to three industry professionals that served as managers and booking agents for ABB and Betts’ solo lineups.

“It’s insurmountable,” said Bert Holman, manager of the Allman Brothers and protector of their brand over the past 35 years. “He was one of the original six that became the band. Dickey was a great songwriter and guitarist, a unique vocalist; a pillar foundation of the creation of the Allman Brothers and its sound. We can never not acknowledge it.”

PEACH FUZZ: Dickey Betts’ final public performance at Peach Fest in 2018. (Courtesy Ike Richman)

Charlie Brusco, manager of the Marshall Tucker Band and The Outlaws for Red Light Management, booked Dickey Betts from about 2010-12 with David Spero, who served as Betts’ manager for the past 23 years. Last week, Brusco made a point of contacting Doug Gray and Henry Paul, original members of MTB and The Outlaws and still touring with those entities, to inform them of Betts’ passing before the news broke online.

Gray and Paul both knew Betts from touring together in the 1970s, as well as Brusco, who lived in Macon, Georgia during his first go-around managing The Outlaws during that era. Macon, a city rich in musical history, was ground zero for the southern rock scene and the home of Capricorn Records, where the Allmans and Marshall Tucker had record contracts, and where the ABB family lived at the “Big House” in town for three years.

Betts’ contemporaries, guitarists such as Lynyrd Skynyrd’s Gary Rossington and Allen Collins, and The Outlaws’ Huey Thomasson and Billy Jones, looked up to Betts as they established their careers, Brusco said. They all recognized that Betts was the glue that kept the Allman Brothers together after the death of both Duane Allman and original bass player Berry Oakley in 1972 in a separate motorcycle accident.

Starting with 1973’s “Brothers and Sisters,” the first album the Allman Brothers recorded without Duane Allman’s contribution and which included Betts’ hit song, “Ramblin’ Man,” which he called his “throwaway country song,” Betts began to take control of a band that became adrift after those two setbacks and needed to regain its footing as a rock group and touring entity.

“Dickey was the main part of how they got through all that (turmoil), and he was unassuming in how he did it,” Brusco said. “If you look at all the different musical styles that Dickey played, whether it was bluegrass, country, rock or blues, it’s not easy to navigate all that stuff and be respected like he was. Dickey’s mark is all over everything from the beginning to the end of the Allman Brothers.”

Alex Hodges, CEO of Nederlander Concerts, was there at the beginning, relocating to Macon in the spring of 1970 to join his friend, Phil Walden, co-founder of Capricorn Records.

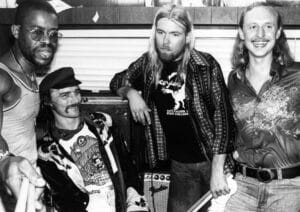

CORE FOUR: Jaimoe, from left, Dickey Betts, Gregg Allman and Butch Trucks, shown here in an archival photo, carried on with the Allman Brothers Band after lead guitarist Duane Allman and bass player Berry Oakley died in the early ’70s. (Getty Images)

Over the next several years, Hodges became a booking agent for the Allman Brothers. It all started after ABB played a small club in Atlanta, where Hodges had previously lived and witnessed the band’s performance. Walden handed Hodges an acetate of their first album, told him to listen to it and move to Macon if he liked it.

“I felt the tapestry of the music, the inner weaving of the instruments — two guitars, a Hammond B3 organ — and it was unbelievable,” Hodges said. “The vocals from Gregg and Dickey were fabulous. It was a mixture of blues, rock, jazz and country. Phil knew what he had and the band knew what they were doing. It first came together at that tiny club in Atlanta.”

Holman grew up as a big Allman Brothers fan in the early 1970s. He saw the original lineup play, including their historic performances at Fillmore East in New York, and remembers Dickey Betts standing toe to toe with Duane Allman, trading licks on stage.

“When they played live, it was ferocious; it was like a friendly duel every night,” Holman said.

Holman’s business relationship with Betts dates to 1981-82 after promoter John Scher with Metropolitan Entertainment took over management of the Allman Brothers. Holman was Metropolitan’s No. 2 guy, and it came at a time when the core Allman Brothers lineup had broken up again, leaving the individual members on their own to make a living.

At the time, Betts had formed an offshoot with ABB drummer Butch Trucks and Chuck Leavell, their keyboard player, along with Jimmy Hall from Wet Willie. Betts, Hall, Leavell and Trucks toured for a few years during the punk and new wave era before splitting up after Leavell joined the Rolling Stones and Hall focused on collaborating with Jeff Beck. Holman was in charge of booking the group.

“The problem was that band was swimming upstream in that style of music,” Holman said. “It was a powerful band, but it wasn’t the right time musically. We weren’t the (right) flavor. We had a core audience, able to play to 1,000 people a night, but couldn’t get over the hump.”

In 1989, the core four of the Allman Brothers, Betts, Trucks, Gregg Allman and Jaimoe, reformed after releasing the box set “Dreams,” which resulted in a short tour before the band recorded a new album, “Seven Turns,” released in 1990. The record marked a rebirth for the band that many in the mainstream media thought was past its prime after so many disintegrations.

ABB, with new members Warren Haynes, who was part of the Dickey Betts Band, and Allen Woody, got back in the groove by playing a series of club and theater dates, which included the first of what would become annual extended runs at the Beacon Theatre in New York.

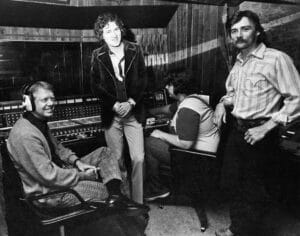

ROCK THE VOTE: Jimmy Carter, left, then governor of Georgia in 1974, visits with Capricorn Records’ Phil Walden and Dickey Betts during the production of Betts’ solo debut album “Highway Call.” (Getty Images)

Holman said the intent was to recapture the vibe of the old Fillmore East, the venue where ABB recorded its landmark live album in 1971, which stands along the greatest live rock performances of all time. Holman was lucky enough to attend that show.

Returning to the smaller venues that originally put them on the map worked. The response was positive for a group that regained its chops after not performing together basically since 1982, Holman said.

For the next 25 years, a rejuvenated ABB went on to fill amphitheaters nationwide on summer tours, plus the annual three-week springtime residencies at the Beacon.

From 1981-99, the Allman Brothers sold more than 3.2 million tickets from 510 shows, with gross ticket sales surpassing $75 million, which equates to $140 million in 2024 dollars, reported by VenuesNow/Pollstar box office liaison Bob Allen.

Dickey Betts was principally involved in getting the band back together in the early ’90s, said Holman, who first started with ABB as tour manager before taking over as manager in an atypical agreement.

“They came up with this concept that they wanted to manage themselves,” he said. “But they knew they were unmanageable and weren’t capable of doing the work. They wanted someone to focus on them instead of juggling multiple acts. They hired me as the manager and made me an equity partner in the bottom line. That was in 1991, and here I am, still standing, much to my amazement.”

For Betts, the end of his tenure with the Allman Brothers came in 2000 after Holman said his “personal habits” began to affect the band’s performances. The three remaining equity partners, Gregg Allman, Butch Trucks and Jaimoe, sent Betts a message asking him to take the summer off to pull himself together before returning to the band. Betts said publicly he was “fired by fax,” but that was not the case, Holman said.

“He needed to regroup and had done that once or twice before over the years,” Holman said. “Dickey managed to do something that I’ve never seen anybody else do, which is get Gregg, Jaimoe and Butch to agree on something. He resented that (message). Dickey lived hard. The bigger problem was Dickey was losing his hearing. He was playing unbelievably loud, because he couldn’t hear, and it got to the point where he was drowning everybody else on stage.”

Ultimately, the situation over Betts leaving the band went to arbitration, and as one of the four primary shareholders, he was awarded a financial settlement to complete the separation. Gregg Allman, Butch Trucks and Jaimoe were satisfied with the agreement, Holman said, and ABB went on to perform another 14 years with multiple replacements, including guitarist Derek Trucks, the nephew of Butch Trucks.

PLACE YOUR BETTS: Duane Betts, left, joins his father Dickey Betts as Great Southern performs a 2012 concert in Barcelona, Spain. (Getty Images)

Dickey Betts’ final chapter covered playing festivals and clubs with Great Southern and the Dickey Betts Band, including the Variety Playhouse in Atlanta, the Neighborhood Theatre in Charlotte and House of Blues in other markets. His son, Duane Betts, joined his father’s band before carving his own career with the Allman Betts Band, teaming with Devon Allman, Gregg’s son.

Dickey’s final public performance at the 2018 Peach Fest, an Allman Brothers-centric festival at Montage Mountain in Scranton, Pennsylvania. He was joined onstage by Duane and Devon.

The musical tributes poured in after Betts’ death. Billy Strings honored Betts by performing his signature song, “Ramblin’ Man,” as well as “Sweet Martha,” written by Duane Allman, during his three-night run (April 19-21) at the St. Augustine Amphitheatre in Florida. In Gautier, Mississippi, on April 19, North Mississippi All-Stars guitarist Luther Dickinson joined Jason Isbell and the 400 Unit to perform “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed,” the instrumental jam written by Betts.

Elsewhere, Live Dead and Brothers, showcasing the talents of guitarist Les Dudek, 71, who played on “Brothers and Sisters,” is currently on a 16-date tour, through May 11. The group, which includes bassist Berry Duane Oakley, son of Berry Oakley, is breathing new life into Grateful Dead tracks and ABB classics written by Betts, such as “Blue Sky” and “Jessica,” the latter of which Dudek shares a songwriting credit.

“It’s remarkable what a great songwriter Dickey was,” Hodges said. “I think of those songs and I play them all the time and I’ll keep playing them even more. Dickey was one of a kind. I’m thinking of “Pony Boy” (and the lyrics) ‘When morning comes and it’s time to go, Pony Boy, carry me home.’ This one was always special to me.”

Apart from his songwriting abilities, Dickey Betts ranks with the greatest rock guitarists such as Eric Clapton and Jimmy Page, Brusco said.

“Dickey’s on the same level with those guys; it’s not just a southern rock thing,” he said. “He was so much more than that, the full deal. He wasn’t pigeonholed into one kind of playing. He could make that guitar talk. The music that those guys made will outlive us all.”

Editor’s Note: Pollstar features editor Debbie Speer contributed to this story, which has been updated.