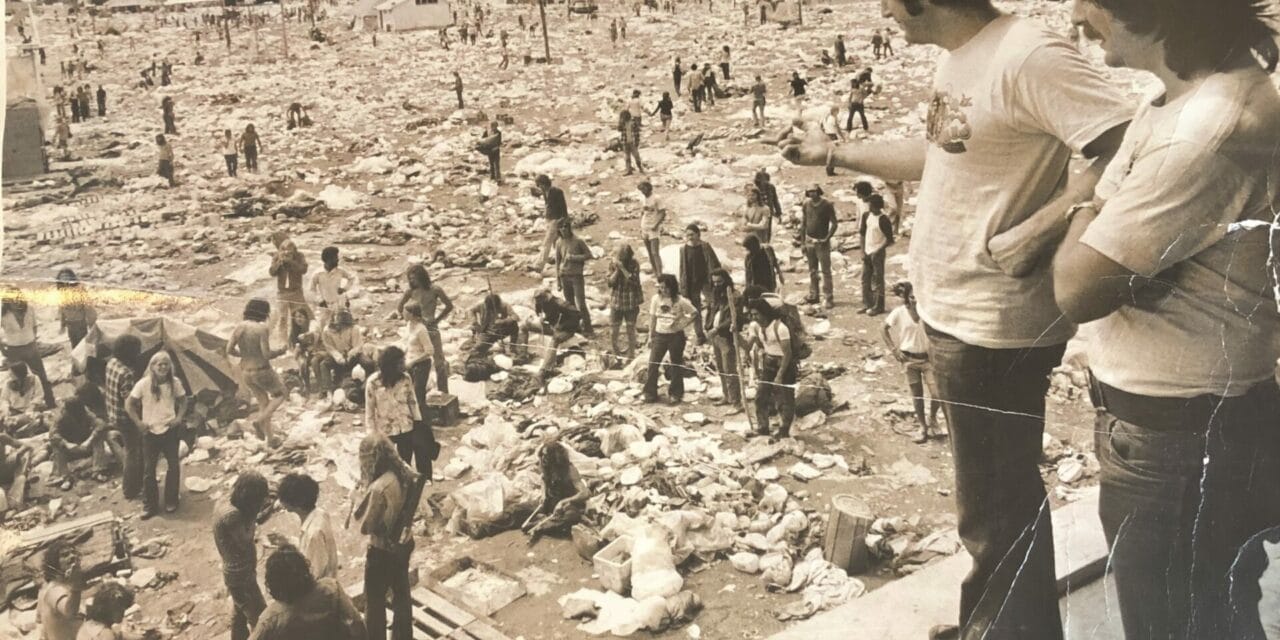

The morning after: Shelly Finkel, left, and Jimmy Koplik exchange pleasantries with fans in the aftermath of Summer Jam ‘73 at Watkins Glen.

Jimmy Koplik points to multiple landmark concerts he’s promoted over 53 years in the live music biz.

A few shows that stand out include The Eagles, Heart and Little River Band before 70,000 at the Yale Bowl in 1980, and “Last Play at Shea” in 2008, featuring Billy Joel, Garth Brooks, John Mayer, John Mellencamp, Paul McCartney and others at the New York Mets’ old ballpark.

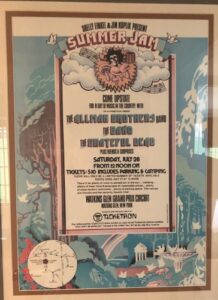

But nothing compares to Summer Jam ‘73 at Watkins Glen International, a Formula 1 racing facility in upstate New York. The Allman Brothers Band, Grateful Dead, The Band and Leon Russell played before a crowd of 600,000, the largest attendance for a concert in U.S. history.

The July 28, 1973 show came four years after Woodstock ‘69, a three-day festival, set the bar for massive concerts.

“I give Woodstock all the credit in the world because it was a cultural event,” Koplik said. “Ours was just a bigger event.”

As a single-day show, Summer Jam was never planned as a festival but ended up categorized as one due to its sheer size. Plus, it unofficially started the day before the Saturday performances, Koplik said.

“We had 200,000 people there on Friday,” he said. “The artists made it that way because the sound checks were almost as long as their full sets on Saturday.”

Koplik and Shelly Finkel, his business partner, were both in the early stages of their career as concert promoters. At the time, they were both “young and dumb” for thinking they could pull it off, Koplik said.

They were just young and dumb enough to generate a hefty profit at the end.

“I’m very proud to say we might have been the first festival to actually make money,” he said. “Shelly and I each walked away with a check for $250,000, which was very nice.”

Looking back, Koplik said they were ill prepared for what turned into a monster event.

Luckily, they had Bill Graham advising them because he had a close relationship with the Dead. They had an open line of communication with the godfather of concert promoters for any issues that arose at Watkins Glen.

Graham co-owned a business with Barry Imhoff called FM Productions, named for the Fillmore venues owned by Graham. It was one of the first companies to build stages and back-of-house facilities for one-off events. Koplik/ Finkel paid them $200,000 to construct the compound.

The promoters expected a crowd of less than half of the estimated number that actually showed up for the concert.

“We planned it, but it was an accident,” Finkel said. “We thought 250,000 people would show up. But it was 600,000 and might have been more because they (closed) the New York State Thruway and turned people around. At one point, it was backed up 100 miles.”

“No one could plan for that,” he said. “If they could, I would have figured out a way to sell tickets to everyone. It was a mellow crowd; they came to see the show. No violence. It just got out of hand in certain ways and the preparation could not accommodate everyone who showed up.”

The track at Watkins Glen had played host to big crowds in the past with auto racing and venue owner Henry Valent was eager to book another event, Koplik said. Valent was paid $100,000 to rent the track, which is a little more than $1 million in today’s currency, he said.

The town itself was tiny with 1,300 residents and didn’t generate much revenue apart from Grand Prix weekend.

“We always kidded around that they generated six months of income on one weekend,” Koplik said.

“This concert would make their year because we created another big weekend. That really did win the town over and got us through the board and secured our permit.”

One person died at the event and it wasn’t directly tied to the crowd on the ground.

The incident occurred after four skydivers jumped from a plane holding flares to mark their descent. Willard Smith, one of those skydivers, was found burned to death in a wooded area near the concert site.

The flare apparently ignited his clothes on the way down, the New York Times reported the day after the concert.

For Last Play at Shea, a two-day event, Koplik was running Live Nation’s New York office at the time and he was asked to help produce the show. It was a special moment for Koplik.

The thing he remembers most was McCartney’s last-second appearance on July 18, 2008, the second of two nights of live music at Shea Stadium, which was torn down months later and is now a parking lot for Citi Field.

McCartney flew from London, England for the concert but was running late. His flight landed at John F. Kennedy International Airport at about 10:30 p.m. that night. The curfew at Shea was 11 p.m., “which we were going to break anyway if we had to,” Koplik said.

“He lands and I look at Dennis Arfa (Billy Joel’s agent) and say he’ll never make it here on time,” he said. “I forgot he was ‘Sir’ Paul McCartney and apparently he did not have to go through customs. I don’t know exactly how it worked but he got picked up right on the tarmac and got a police escort down the Long Island Expressway to the show.”

McCartney made it to the ballpark in 15 minutes, just in time to perform with Billy Joel.

“I remember him pulling in and couldn’t believe he was there,” Koplik said.

For Koplik, two concerts stand out for never happening, aside from Summer Jam West.

One event was the Allman Brothers, booked for Nov. 16, 1971 at New Haven (Conn.) Arena. It was to be Koplik’s first concert promotion since he went out on his own, shortly before forming a partnership with Finkel.

“It ended up that Duane Allman was killed in a motorcycle accident a few weeks before (Oct. 29) and my show got canceled,” Koplik said. Allman, Gregg’s older brother, was the band’s lead guitarist.

The one act he always wanted to promote but never got the opportunity was the incomparable Jimi Hendrix. Koplik had a date set for Columbus, Ohio as part of his 1970 “Cry of Love” tour.

The May 24 show at Veterans Memorial Auditorium was canceled after Hendrix “had too much of something the night before and couldn’t get to my show,” Koplik said.

About four months later, Hendrix died Sept. 18, 1970, of complications from a drug overdose.