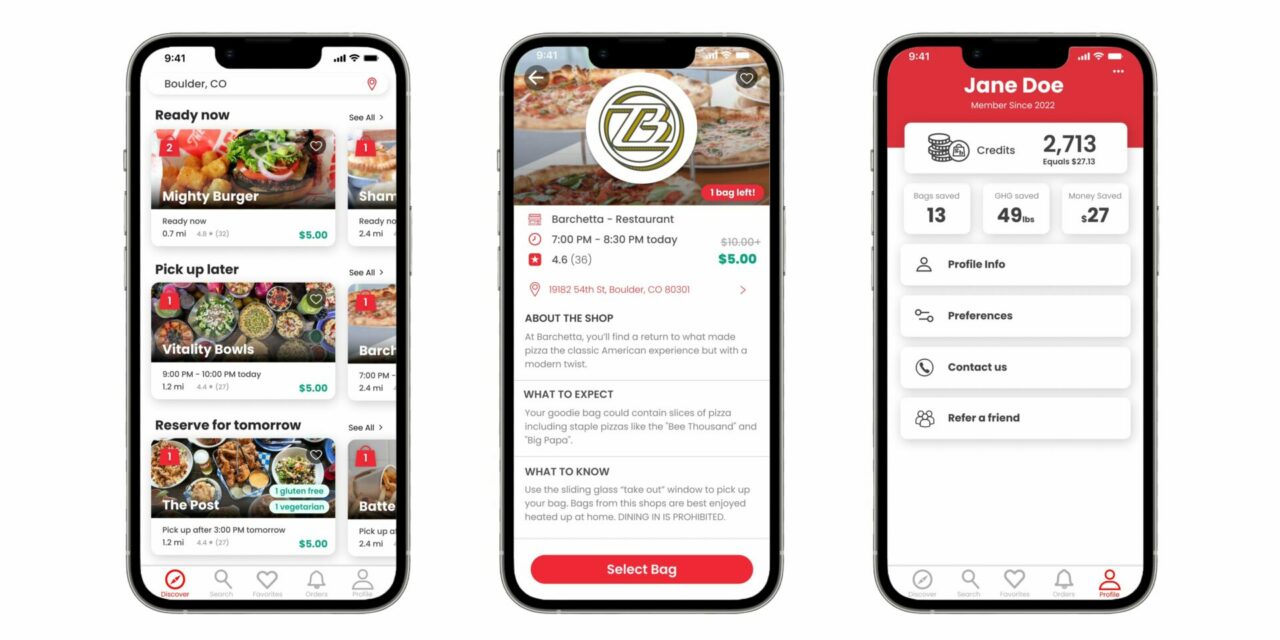

GOODIE WORKS: Goodie Bag’s mobile application is the starting point for providing affordable meals for customers and helping restaurants cut down on food waste. (Courtesy vendor)

Potential solution for food waste at arenas and stadiums

A mobile tech startup that helps restaurants reduce food waste by repackaging and selling leftovers at an affordable price has some in the food service industry believing the concept could be applied to sports and entertainment venues.

Goodie Bag, a Boulder, Colorado firm launched in January 2023 by two young entrepreneurs, Eddy Connors and Luke Siegert, has deals with locally owned eateries in Boulder, Denver and Fort Collins, Colorado, and is expanding to Charlotte, North Carolina and Phoenix, Arizona in the coming weeks.

To this point, Goodie Bag’s clients are mostly bakeries and pizzerias, said co-founder and CEO Connors, a 2022 University of Colorado graduate.

The company is tied to a mobile application in which customers register for the opportunity to purchase a small bag of food that costs between $3 and $10. The average transaction is $6, Connors said.

Those items are typically surplus items that would otherwise get thrown in the trash.

Customers don’t know in advance the exact items contained in the bag, other than the restaurant it came from. In those markets where Goodie Bag is operating, customers are notified through the app of their availability and whoever is first to press the pay button gets to pick up the food at the restaurant.

“The shops mix and match what they have left over to create that bag and value,” Connors said. “You can get a full meal at that low cost, which is pretty unheard of these days. There’s limited availability, and often, they’re gone in minutes because it’s such a great deal.”

Over the first year of operation, Goodie Bag has “saved” more than 5,000 meals for its 50-plus restaurant partners, according to Connors. Under its business model, Goodie Bag keeps 30% of every transaction and the restaurants capture the remaining balance. The service is free for both the participating restaurants and Goodie Bag customers; nothing comes out of their pockets and there are no hidden fees for the consumer, he said.

Goodie Bag’s first partner, a Boulder pizzeria named Barchetta, salvaged $4,000 over the past year in what otherwise would have been sunk costs by selling leftover slices from lunch hour that were boxed up and put in the fridge until customers picked them up. In an industry where margins are typically razor thin for mom and pop shops, that’s no small change, Connors said.

“Our customers could pick up half to a full pie for (about) $6,” he said. “People liked it, the restaurant liked it. It felt good to bring value, and at the same time, have customers buy quality food at an affordable price.”

For arenas and stadiums, some industry experts believe there could be a role for Goodie Bag to play for concessionaires that contend with surplus food after every event, whether it’s in the suites and clubs or general concessions.

The logistical issues for customer pickup would have to be resolved and some food providers may not want to get into the business of being a “mini-restaurant” after the game, said consultant Chris Bigelow.

Conversely, it could provide another option to resolve overproduction at public assembly venues, Bigelow said.

Some vendors give leftovers to food banks and other resources to feed their patrons, and many have composting programs. In some cases, employees can take food home after an event, but overall, a lot of food does get wasted, whether it’s the big leagues, minor leagues or the college level, Bigelow said.

“In the old days in minor league baseball, if a fan waited until the eighth inning, the team may announce that hot dogs were reduced to $1,” he said. “Then, they realized fans got smart to this and they’d wait until late in the game to buy their hot dogs, so it may not have been a great idea. But that’s the only time I saw when they tried to do some kind of clearance toward the end of the game.”

Jonathan Harris, another consultant, said a concept such as Goodie Bag could work in a sports and entertainment setting, particularly in premium spaces, where food is prepared and constructed in a “ready to eat” format.

“I could envision a scenario where this group can set up a defined partnership, which would allow teams and concessionaires to plan ahead (for surplus distribution) based on facility schedules, which would be a win-win for everyone,” Harris said.

Scott Jenkins, vice president of facility development for the Kansas City Current, a National Women’s Soccer League team and new CPKC Stadium, and board chair for the Green Sports Alliance, loves Goodie Bag’s vision, but he said it can be a hurdle getting people to buy food when they don’t know it is.

The savings involved, a minimum of 50% on each order compared with the regular cost of those items on the restaurant’s menu, helps alleviate that barrier, Connors said.

Goodie Bag principals are taking it slowly as they enter their second year of operation. As part of growing the business, they’re working with universities in each market.

In Charlotte, as part of the company’s launch in the Carolinas’ biggest market and one of the country’s fastest-growing cities, Goodie Bag is working on a pilot program directly with Chartwells, the vendor that feeds students on the University of North Carolina-Charlotte campus, including the school’s sports facilities.

Chartwells is part of Compass Group, the world’s biggest food service company and whose North American headquarters are in Charlotte. Levy, another Compass Group subsidiary, has deals at dozens of big league facilities, and those connections could potentially provide an entry into the venues world, Connors said.

It’s up to the customer to go pick up their food order, and Connors said there would have to enough event attendees that use the Goodie Bag app to meet demand.

For Goodie Bag, it’s appropriate that the college space plays a key role in the company’s evolution.

Connors and Siegert have both worked at restaurants and saw firsthand from experience when food items were “overprepped” and wrong orders were made in the kitchen, as well as no-shows for carry-out orders.

They met as Colorado students and Connors remembers the “classic Raman noodle diet” common among cash-strapped college students trying to stretch a buck and get fed at the same time.

Putting their heads together, they discovered there was a niche to be filled to connect unsold product with customers willing to purchase it at a discount price.

“Many students are on a tight budget and limited in options for what they’re able to spend,” he said. “We didn’t want people to sacrifice quality.”

Another plus for Goodie Bag is reconnecting consumers with brick-and-mortar businesses in a post-pandemic world.

“Something that’s big for our culture is recognizing the influence some of these delivery services have had, which has fragmented a lot of our community interactions,” Connors said. “We want to be someone that goes against that trend and brings people back physically into stores, talking with local owners and supporting the economy in a way that’s sustainable financially and environmentally.”