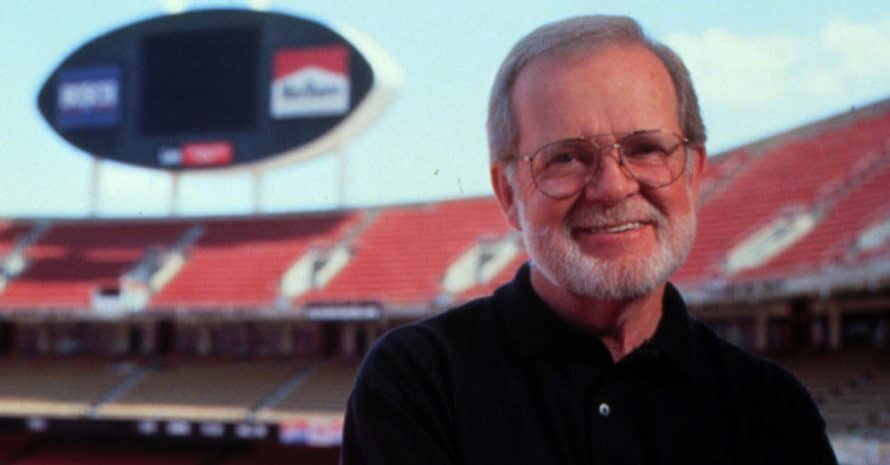

HALLOWED GROUND: Ron Labinski, shown at Arrowhead Stadium, the first sports facility he designed that inspired him to create a practice to develop arenas and stadiums. (Courtesy Populous)

“He set the gold standard for putting together an NFL market.”

Ron Labinski, considered the godfather of sports venue design and a savvy architect with the vision to launch a practice tied exclusively to arena and stadium development, which ultimately became a multibillion dollar industry, died on New Year’s Day. He was 86.

Labinski stood out as co-founder of the old HOK Sport in 1983, a Kansas City, Missouri firm that went on to dominate the design of facilities across the globe, and whose influence carried over to hundreds of sports architects that followed his career path.

“He was our spiritual leader,” said Earl Santee, global chairman, senior principal and founder of Populous, which the old HOK Sport morphed into and rebranded in 2009. “He taught us how to love the work and love working together. That’s an important part of our culture. What he started is still a big part of our practice today.”

Apart from Populous, most sports architects at other firms point to Labinski as having the greatest impact on the business, said Tom Waggoner, a 40-year sports designer and the author of “Designed in Kansas City: How Kansas City Became the Sports Architecture Capital of the World.”

Labinski effectively retired in 2000. Waggoner interviewed 35 architects across multiple firms for the book that was published in 2021.

“To our good fortune, we owe Ron a debt of gratitude and a tip of the hat at least,” Waggoner said. “He was out there fighting and trying to do it for himself for the emerging firms that many of us followed. In the book, (sports designer) Bill Johnson said, ‘Ron was the guy we put a target on. We all respected him and he set the gold standard in terms of putting together an NFL market and all the other markets that grew out of that.’”

Ron Turner, a principal and global director of sports and entertainment with Gensler and now an elder statesman within the sports design community, worked with Labinski at the old DJLM and HNTB. Turner said his skills in building sports practices on his own can be directly attributed to Labinski’s guidance in the 1970s and early ’80s.

“His innovation and leadership has made it possible for me and many architects to build lasting careers,” Turner said.

Jim Steeg, who served as the NFL’s senior vice president of special events for 26 years, knew Labinski well, dating to the build-out of Stanford Stadium for Super Bowl XIX in 1985.

“He was one of the foundations on which the modern NFL was built,” Steeg said. “It started with (Arrowhead) Stadium and changed all of the design of stadiums.”

In the late 1960s, Labinski was a young designer with the old Kivett & Myers. Sports architecture as a discipline did not exist until Truman Sports Complex opened in Kansas City in 1972-73 with separate purpose-built stadiums for the NFL Chiefs and Major League Baseball’s Royals. Labinski worked on that project which got him thinking about opportunities to design NFL stadiums in other markets.

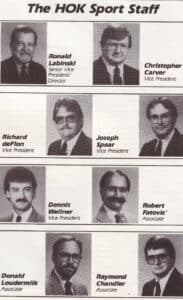

He compiled a list of all teams and the years their leases expired at publicly–owned buildings, targeting those prospects and establishing relationships with team owners, said Joe Spear, who worked across three firms with Labinski and co-founded HOK Sport, along with Dennis Wellner, Rick deFlon, both now retired, and Chris Carver, still active with Populous and part of the Climate Pledge Arena design team.

During the 1970s and early ’80s, through a series of moves that included jumping back and forth between HNTB, plus forming Devine, James, Labinski and Myers (DJLM), a much smaller company, Labinski and his core group gravitated to sports. Their early projects included designing Giants Stadium at the New Jersey Meadowlands and the Hoosier Dome, plus several suite retrofits at existing facilities, Spear said.

In December 1983, they signed a landmark deal with HOK corporate in St. Louis to start a sports practice headquartered in Kansas City. The group’s workload for planning new facilities from the ground up took off, starting with Joe Robbie Stadium, now Hard Rock Stadium, followed by more than a dozen NFL and MLB venues during the building boom of the 1990s and early 2000s.

“Ron was able to see things that other people didn’t,” said Spear, a top designer of MLB parks and now semi-retired. “He was able to understand the business and the sport, particularly in the NFL, and most teams considered him almost a part of the league. They all loved him. When he made a suggestion, they all took it very seriously and that says a lot about the man.”

Don Loudermilk, part of the original HOK Sport, said Labinski single-handedly made sports venue design a viable industry. No one else dreamed it could be a separate sector until Labinski pushed the concept and convinced team owners there was something better for them in facility development, Loudermilk said.

“When I first joined him, it was DJLM and we would all wander by his desk and see these drawings of stadiums,” he said. “We all got curious and wanted to know what the heck he was doing. At the time, it was just him really doing it. As his efforts grew, we all couldn’t wait to get involved.”

GANG OF EIGHT: The original HOK Sport staff, shown here in 1987 as part of a story in the old Performance magazine. (Courtesy Bob Fatovic)

At the beginning, Spear had doubts about whether the focus on sports venue design could sustain itself over time. The group all heard the chatter from team owners telling them it wouldn’t last after every club got a new building.

“It seemed like every year, someone told us it was going to die the next day,” Loudermilk said. “Ron had faith in it and we stuck with him. He wasn’t a great manager or administrator, but a hell of a leader and a visionary.”

Labinski had a flair for business development, and he was always one step ahead of the game, strategizing about how to win the next project, which became critical to maintaining a steady flow of business, Spear said.

“He understood what it took to make an architectural practice hum,” he said. “Marketing was his forte and he was great at it.”

It took tenacity to carve that niche, said Chris Lamberth, head of sports and public assembly design at TVS.

“To me, what they built is not what I think of, it’s where they came from,” Lamberth said. “He’s an example of persistence: Here’s a niche, a market, we can go do it and he did it with a small group of guys.”

On the construction side, Hunt Construction Group, now AECOM Hunt, built more than 60 sports venues designed by HOK Sport, all connected to the Labinski lineage of architects, said Ken Johnson, the general contractor’s president of the central region.

“We really cut our teeth with Ron and his colleagues in the early days … to build some of the most iconic stadiums in the U.S.,” Johnson said. “He inspired a whole generation of young builders to construct the best project they possibly could.”

It helped that over time, Labinski got to know practically everybody in the industry. He made a point to build long-term relationships to grow the practice, which is the right to do it, said George Heinlein, a retired sports architect who got his start at HOK Sport in the late 1980s.

“I have a great amount of respect for what he built at the original HOK,” Heinlein said. “He will be missed.”

Heinlein and Bob Fatovic, employee “No. 7” in the original group that formed HOK Sport, both said Labinski served as a mentor who took them under his wing in the initial stages of their careers. Both traveled with Labinski overseas to design arenas in the U.K., as he began to expand business internationally, including a merger with Lobb Sports Architecture in the late 1990s.

On his own, Fatovic, now a consultant, spent four years in London working on projects won by Labinski. Together, they traveled Europe and went to Germany for the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989.

They each got a piece of the wall. For Labinski, it was an emotional experience, Fatovic said, considering he was an Army veteran that had been stationed at Fort Riley, Kansas, two hours west of Kansas City.

“He was an incredible guy,” Fatovic said. “I owe him so much.”

The same is true for Nate Appleman, vice president and director of HOK Sport, Recreation and Event, which re-entered sports architecture in 2015 after signing a non-compete as part of the separation agreement with the group that would form Populous.

Before Appleman decided to pursue sports architecture as a career in the late 1990s, he researched the industry and it became apparent that the old HOK Sport had great influence, led by Labinski. Appleman was fortunate to start his career at that firm, where he spent about 14 years before moving to 360 Architecture, now part of HOK Sport, Recreation and Event.

“Getting an offer to work there was a dream come true,” Appleman said. “Ron was a genuine person. Sometimes, you get worried about people that get into that position of power and influence. He always had that kind of devilish grin, but he was down to earth. If you made a connection with Ron, he was going to be with you no matter which acronym was after your name. That’s hard to come by.”

Editor’s Note: This story has been updated.