LEEDING EDGE: Golden 1 Center, shown here during a Sacramento Kings game in January and the first indoor sports venue to earn LEED Platinum, is an ABM Industries client. (Getty Images)

Keep recycling efforts simple, not stupid

Education and professional development are among many challenges facing the sustainability industry in sports and entertainment. Event schedules and the dynamic nature of venues post-COVID makes it difficult to stay in front of the flow of information, new technology and staying abreast of new programs being used around the country.

“Professional development is hard, because in a lot of cases, we are moving so quickly,” said Brian Grant, director of operations for national sports and entertainment at ABM Industries.

ABM Industries, a provider of professional office services such as janitorial, electrical and lighting, HVAC, landscaping and parking, started in 1909 as a one-man window-washing operation in San Francisco. Over the past century, it has a grown to 100,000 employees in 250 locations. Clean equals green for ABM, which provides a variety of services for stadiums and arenas including California’s Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, Golden 1 Center in and SoFi Stadium.

“Five to 10 years ago, sustainability might have been a nice goal for the environment, but from my perspective, there are some actual, tangible, financial benefits to being sustainable with the way that we manage these large-scale venues,” Grant said. “I think there’s a unique niche culture around these venues. From where I sit, my goal would be to benefit anybody else who is struggling with these decisions. Connecting people is where we find that value.”

The cost of a kilowatt or megawatt hour is significant and venues can make a difference by reducing that expense. Methods to do so include by lowering lighting consumption with on-demand or dynamic lighting schedules. or adjusting the amount of heating and cooling.

Several years ago, LA Memorial Coliseum, home to USC Trojans football with a capacity of 77,500, started a zero-waste program.

“People were happy to support it, but it came down to ‘How can we make it not cost me any money?” Grant recalled. “Because on some level, we were going to add labor to make sure all that waste was properly sorted and distributed. And we were going to have cost changes.”

At the time, it was cheaper for venues to order non-compostable, non-recyclable materials, with the food and beverage partner absorbing additional costs. The discussion was how to keep from affecting consumers by passing on those expenses. Sponsors stepped up to cover the added costs, including ABM and supply-side partners and waste haulers. With the value of the recycling commodity, plastic and aluminum, Grant said they were able to go to the general manager and say the program would be “cost neutral, at worst.”

The program is now diverting waste; 90% is a baseline of what is considered zero waste. Engaging fans in the process meant minimizing the number of decisions fans needed to make.

“We didn’t want to create confusion about where any particular item ended up in the waste stream,” Grant explained. “So, the coliseum doesn’t recognize trash. There is no such thing as trash on their concourse. It’s just compost and recycling. It came down to if I eat it, I compost it. If I drink it, I recycle it. That’s as simple as it’s going to be.”

Reducing waste decisions encouraged fan participation.

Brian Grant, ABM Industries

“That program really took that model of ‘How can we do something sustainable? How can we be responsible?’ — both on the environmental impact side and the financial side — and make those two ends meet,” Grant said. “People bonded together and found ways to be creative and make something that at one point was a cost, but really came out neutral in the end.”

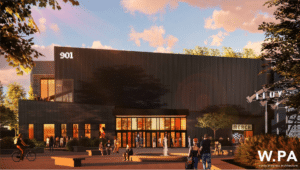

At Golden 1 Center, home to the NBA Sacramento Kings with a capacity of 17,608, ABM provides a bundle of services, including janitorial, engineering and parking. The arena opened in the fall of 2016 and ABM joined the team early in the construction process. Reaching LEED Platinum, the highest certification under the U.S. Green Building Council’s program, and establishing processes to support sustainability were an early priority.

With rooftop solar energy, Golden 1 generates enough energy to donate back to the power grid servicing Sacramento. On-demand and predictive modeling makes it possible, with artificial intelligence and metrics, to optimize energy demands and timing for heating and cooling the building, which takes up 1 million cubic feet.

“There is better data behind some of the decisions that we are making, which allows us to be more sustainable and make more educated decisions with the information that we have,” Grant said. “It allows us to be really tailored in how we manage the venue.’

With technology, the collection and distribution of information has never been easier.

SoFi Stadium, which opened in 2020 and can accommodate up to 100,240 patrons for concerts on the field, has a “digital twin,” which is a virtual representation of a system, encompassing mechanical, electrical and plumbing systems. It is updated from real-time data and uses simulation, machine learning and reasoning to help decision making.

“It allows them to see things in real time, a predictive model, that allows them to make more educated decisions,” Grant said.

A big priority for the venue was water management in drought-prone southern California. The stadium, home to the NFL Los Angeles Rams and LA Chargers, was built with a massive cistern under the building that collects rainwater runoff. The reclaimed water can be used for irrigation and donated back to the community. Another consideration was “heat sink” and supplementing heat-absorbing asphalt parking lots with green spaces. Heat in the building can be vented through roof panels, similar to a sunroof in a vehicle.

“That’s what gets lost in the sustainability discussion. Any amount of progress is good,” Grant said. “So, let’s start with that.”