IN THE MIDDLE: Express Live! in Columbus, Ohio, opened in 2001 and provides a middle-tier capacity option for the market with both inside and outside stages. (Brian Hockensmith Photography / Courtesy PromoWest Productions)

The so-called secondary markets may not have the cachet of New York, Los Angeles or Chicago, but regardless of the term one uses to describe midsize and smaller cities, they can be key cogs in the gearworks of live tours, like the current Guns N’ Roses outing, with robust ticket sales and an outsized economic and cultural impact.

When it comes to navigating the quirks of Albuquerque or doing business in Birmingham, agents, talent buyers and venue operators balance the challenges and opportunities present in their respective markets, often thanks to years or even decades of experience bringing in bands, comedians, family entertainment and more.

CHART: Tickets Sold and Grosses From a Selection of Secondary Markets

So what’s a secondary concert market? There’s not a tidy list to go by, but one thing we kept in mind as we picked markets for our chart and discussed in this story: They’re not stops on all the major national tours, but they’re on some or most of them and competing for nearly all of them.

The markets discussed here fall between roughly a million and 2 million people in population. The vast majority accounted for 1 million to 4 million tickets sold 2015-19, according to Pollstar box-office reports. Total grosses varied more widely, affected as you might expect by differences in the cost of living around the country.

Perhaps most important: This is not a complete list but a selection of markets that fit our criteria and allow us to tell the story of the issues that secondary markets across the U.S. are facing.

Factors from availability, capacity, past performance and personal relationships are all contributing factors in the calculus of tour routing, says Todd Hunt, formerly executive director of BancorpSouth Arena and Conference Center in Tupelo, Mississippi, and now senior vice president of Venue Coalition, a group that helps smaller arenas and theaters book events.

“It comes down to whether the venue can sell tickets,” said Hunt, whose been a talent buyer for more than 30 years.

Knowing the strengths of respective markets is key, he says, but some things hold true regardless.

“Country is traditionally strong in secondary markets, as are family shows,” Hunt said. “Classic rock also works, and we’re seeing an increase in urban shows. Typically, the smaller the market, the closer to the mainstream the show needs to be. It’s hard to sell niche acts at the arena level in markets with smaller population bases.”

Hunt says family shows like Disney on Ice, Monster Jam, Blippi and Baby Shark have done solid business so far in 2021 and have “led the way in terms of ticket selling success stories” as secondary market venues reopen and tours resume following the pandemic shutdown.

“We don’t like to think of ourselves as a secondary market. We like to think of ourselves as becoming a major — maybe not an A+ market, but maybe an A-.” — MIKE GATTO, COLUMBUS ARENA SPORTS AND ENTERTAINMENT

Smaller markets actually enjoy some advantages over larger counterparts, including lower costs for labor and media, Hunt said.

And when a big act does come through, it generates excitement that might be diluted in a bigger city.

“There’s also generally less traffic, so events can stand out more as opposed to competing for attention in the larger markets,” he said. “And during the pandemic, many markets in the middle of the country weren’t saddled with the same restrictions that venues on the coasts endured. This allowed them to attract shows (and fans) that wanted to get back out on the road.”

Hunt says he never imagined a day when the entire touring industry would shut down and now knows “more about infectious diseases, transmission rates, sanitization, air quality, congressional lobbying efforts and many more topics” that weren’t part of his knowledge base prior to March 2020.

“I now know more than ever that live events are an integral part of our human existence,” he said. “Months of living in our bubbles watching events on flat screens reinforced the notion that nothing compares to the live experience, which is great news for our industry.”

Joining with other venues and promoters to package tour stops is another way for secondary markets to make themselves more attractive to agents, some promoters and talent buyers say.

Ryan Northcott, vice president of entertainment and development for LAFC and Banc of California Stadium in Los Angeles, suggests all venues, but especially those in secondary markets, are wise to make shows as turnkey as possible, without adding additional charges, “to have content come in and go right back out to the next town.”

A venue in a particular market that builds a reputation for marketing shows well has the upper hand over those that can’t step up to the plate in that regard, according to Northcott, who has booked arenas and stadiums in markets large and small and managed Citizens Business Bank Arena (now Toyota Arena) in Ontario, California, east of Los Angeles.

“You just keep your head on a swivel and you stay in the game,” Northcott said.

“Those theater operators or club operators, whatever it might be, that are really engaged, that really help out, those are the ones that do best,” he said. “Buildings in smaller markets may be where artists go to rehearse. You become a rehearsal house and that’s an opportunity. That artist is in your place, you’re taking care of them, you’re making them comfortable and you never know when an opportunity presents itself.”

INDIANAPOLIS

One of those markets that could be considered secondary in name only, Indianapolis benefits from its central location between major tour stops in Chicago, Detroit and Nashville. From Lucas Oil Stadium to venues like Ruoff Music Center (originally Deer Creek Music Center) in Noblesville, the Crossroads of America, as Indiana’s state capital is known, gets its share of top acts, says Dan Kemer, former president of Live Nation’s regional office in Indiana and now vice president of programming at the Center for the Performing Arts in Carmel, Indiana.

AMPED UP: Cage the Elephant plays Ruoff Music Center, an amphitheater near Indianapolis with a capacity of nearly 25,000. (Getty Images)

“We are very fortunate to be in a great area geographically for a lot of tours. We’re a few hours from Chicago, we’re a few hours from Cincinnati, a few hours from St. Louis and a few more from Cleveland and Detroit,” Kemer said. “We’re in a unique situation in Indianapolis in that for a lot of tours, whether it’s a primary tour or secondary route, we have a lot of opportunities to pick up dates coming through here, whether it’s artists working from the East Coast looking to get to St. Louis or Denver as a launching pad to get to the West Coast, or north and south working their way down to Atlanta.”

Musical tastes in Indianapolis and across the Midwest have traditionally leaned heavily toward rock and country, but times have changed, Kemer says.

“I would say 20 years ago that was very relevant based on powerhouse radio stations in different markets, whether it be in Indianapolis or Cleveland or Cincinnati, but with terrestrial radio and Spotify and SiriusXM, it really has leveled the playing field on different artists,” he said. “You no longer have to wait to hear the top song in the Top 40 from a particular radio station.”

Still, Kemer describes the dominant Midwest musical diet as “meat and potatoes.”

“They love their rock and roll, their classic rock,” he said. “Indianapolis, in large part due to WTTS, is a pretty dominant Triple A station in the country. You do see a lot more Americana that does very well in Indianapolis compared to other markets that may not have a strong Triple A station. You see an artist like the Avett Brothers. Huge here in Indianapolis and now with terrestrial radio they are doing great everywhere, but Indianapolis was an early champion of the Avett Brothers.”

Eric Neuburger, stadium director at Lucas Oil Stadium, notes that “half the U.S. population lives within a one-day drive of Indianapolis” and for many of them, country and rock still reign.

“So, in addition to our strong local market, we often host scores of traveling fans,” he said.

“Our most successful concerts have been country music acts such as Kenny Chesney, and broadly popular acts such as Taylor Swift and U2. Our biggest challenge for booking large concerts is our schedule full of football, trade shows, marching band competitions and other premier sporting events.”

The stadium’s connectivity with the Indiana Convention Center positions it “as a prime venue for the largest trade shows and conventions that Indianapolis hosts.”

“We’ve also found success with youth sports, marching band and drum corps, as well as traditional sporting events,” Neuburger said.

Lucas Oil Stadium benefits from Indianapolis’ “large-market feel in a tight downtown footprint with walking access to hotels, restaurants and other entertainment venues,” he said.

“Our community was purposely built to host the world’s largest events without the need to rent a car,” Neuburger said.

As for coping with the pandemic, Neuburger says operations proceeded under CDC guidelines in what he described as “a measured approach,” that saw Lucas Oil Stadium host the entire Big Ten Conference men’s basketball tournament (after it was moved from United Center in Chicago) and a large number of NCAA men’s basketball tournament games.

With protocols in place, Indianapolis was able to successfully host NCAA March Madness, “with roughly 25% of those games played at Lucas Oil Stadium, including all Elite Eight and Final Four games,” Neuburger said, adding that “being flexible, relying on long established relationships (and) mutual problem solving were the difference maker in event property owners choosing Lucas Oil Stadium for their most important events during the most challenging times.”

The stadium has a full calendar of music booked for the back end of 2021 and Neuburger says he and his staff “remain poised to adjust to whatever the pandemic throws at us.”

ALBANY, NEW YORK

ECLECTIC MIX: Saratoga Performing Arts Center, part of the Albany, New York, market, springs to life with a wide array of offerings each summer … (Courtesy SPAC)

The Big Apple might get all the glory, but New York is home to multiple other strong music markets. Among them is the state capital of Albany, about three hours north of New York City, which is one of the most reliable tour stops in the Northeast, and sold 2.78 million tickets for a gross $137.9 million between 2015 and 2019, according to Pollstar data.

Key players in the capital city itself include Times Union Center, the configurable arena that in recent years has hosted everything from televangelist Joel Osteen to the rapper DMX, and the Palace Theatre, a staple for major comics like Jerry Seinfeld and Chris Rock as well as esteemed musicians including Bob Dylan and David Byrne.

… and allows for viewing and listening from seats inside or among the trees on the grass. (Shawn LaChapelle / Courtesy SPAC)

But $58.2 million of the market’s $137.9 million figure stemmed from Saratoga Springs, the enclave of 30,000 about 45 minutes north of Albany, which is home to the Saratoga Performing Arts Center. With rock and pop programming curated by Live Nation, the amphitheater is hallowed ground for jam fans: The top 22 box office reports for the venue in Pollstar’s database are held by either Phish or Dave Matthews Band.

But the venue is also acultural and community institution, bringing ballet, classical, jazz and world music to the 55-year-old amphitheater and local affiliates like Skidmore College and Caffè Lena, the enduring 110-seat coffeehouse that once hosted folkies like Pete Seeger and Bob Dylan.

“This is one of the most culturally vibrant small cities anywhere in North America,” said Elizabeth Sobol, who took over as SPAC president and CEO in 2016. “It’s a really extraordinary place. with people who are just music crazy, and 365 days a year, there is a very thriving live music scene here that runs the gamut from jazz to funk to punk and rock to kind of everything.”

While SPAC’s rock programming garners much of the attention – and Sobol emphasized the boon to the local economy such high-profile touring artists provide – it’s more influential regionally than some amphitheaters elsewhere in the country. And, she reminded, while plenty of out-of-towners pour in for artists like Phish, there’s still a sizable local clientele that attends both rock programming and more eclectic fare like New York City Ballet, the Philadelphia Orchestra and Freihofer’s Saratoga Jazz Festival.

“There is not a single person you would meet on the streets in Saratoga that doesn’t have a memory — and 99.9% of them are fond, fond, deep personal memories – about SPAC,” Sobol said.

In major markets like New York City, “you put something really wonderful together and then it makes a tiny little raindrop in the ocean,” she continued. “Here, everything that we do is important to the community. You literally feel a community galvanized around an organization, and that’s incredibly gratifying.”

Plus, when attracting both fans and talent, Saratoga Springs and the Albany market more broadly have some perks.

“You’re three hours from Boston, three hours from Montreal and you’re 30 minutes from Lake George, one of the most beautiful lakes in America, and 45 minutes from 6 million acres of Adirondack parkland – and nobody knows that!” Sobol said. “How is it that people don’t realize this unbelievable, incomparable confluence of awesomeness here in Saratoga?’”

KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI

Shani Tate Ross, vice president, sales and marketing at T-Mobile Center in Kansas City, Missouri says the variety of performance spaces available in that market — “from clubs and theaters/amphitheaters to T-Mobile Center and Arrowhead Stadium” — make for a robust live entertainment environment.

KC AT THE BAT: T-Mobile Center in Kansas City, Mo., prides itself on booking a wide variety of acts, from rapper Travis Scott to rock, classical and R&B.(Getty Images)

“From legacy and heritage acts to newcomers, there are countless examples of artists from all genres — Maroon 5, Drake, Ed Sheeran, Taylor Swift all come to mind quickly — that have grown from playing 200 seat clubs to arenas and eventually stadiums,” she said. “Kansas City is conveniently located at the intersection of North/South (I-35 & I-29) and East/West highways making it an easy stop for tours being routed from Canada to Texas and East Coast to West Coast.”

More than 9 million people are within a four-hour drive of Kansas City, which is a gateway of sorts to and from other large touring markets like Dallas, Denver, St. Louis, Chicago, Minneapolis and others within an eight-hour drive, Tate Ross said.

“At T-Mobile Center, we have been fortunate to consistently book everything from rock to hip-hop, classical, R&B to family shows,” she said.

“By drawing from the 3 million people in the metro (area) as well as being a destination for smaller cities nearby, Kansas City is regarded as a hub in the Midwest,” she said. “The last 18 months have been difficult for our industry. Moving forward, emerging from the pandemic presents artists, promoters and venues the opportunity to re-evaluate how to meet the needs of guests and fans based on new habits and consumption patterns.”

T-Mobile Center works with David Gerardi of Live Nation and Mike DuCharme of AEG Presents, who also book the area’s amphitheaters, including Azura Amphitheatre in Bonner Springs, Kansas, and the outdoor stage across from T-Mobile Center in the Kansas City’s Power & Light Entertainment District, Tate Ross said.

COLUMBUS, OHIO

“We don’t like to think of ourselves as a secondary market,” Mike Gatto said. “We like to think of ourselves as becoming a major – maybe not an A+ market, but maybe an A-.”

Gatto, senior vice president at Columbus Arena Sports and Entertainment, which oversees the Ohio city’s two arenas, Schottenstein Center and Nationwide Arena, has a point. With a population just over 900,000, Columbus ranks as the Buckeye State’s most populous city, and the 14th largest in the country, while its metropolitan area tallies 2.1 million, second to only Cincinnati within Ohio. From 2015 to 2019, 4.16 million tickets were sold in the market for a gross of $238.6 million, according to Pollstar data.

Columbus’ transformation into one of the Midwest’s strongest markets began in the ‘80s, and Scott Stienecker, who founded regional powerhouse promoter PromoWest in 1984, was instrumental in its evolution.

That year, Stienecker, who had recently graduated from Ohio State, caught wind that the beloved 2,000-capacity Agora Ballroom was set to close, and intervened to save the venue. Rechristened as Newport Music Hall, the room today touts itself as “the longest continually running rock club in the country” and has hosted a who’s who of rock and roll, including Neil Young, Pearl Jam and Green Day.

“Every band in the industry has played there,” Stienecker said.

In 1994, PromoWest opened Polaris Amphitheater in Columbus in conjunction with Indianapolis’ Sunshine Promotions, making the market more attractive for major summer tours.

“Columbus people would all drive to either Cleveland to Blossom [Music Center] or they’d drive to Cincinnati to Riverbend [Music Center],” Stienecker said. “Once we built Polaris Amphitheater, Columbus went from secondary to almost a primary, because it became a stop for all these big tours.”

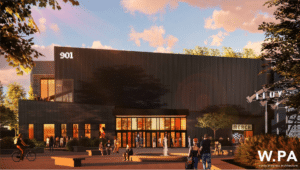

Schottenstein Center and Nationwide Arena opened in 1998 and 2000, respectively, providing the market with two modern arenas. By then, Robert Sillerman and SFX Entertainment had purchased Polaris, and when Stienecker learned the concert magnate was eyeing Newport as well, PromoWest devised what eventually became Express Live!, an innovative indoor-outdoor venue that offered a “bigger Newport” (2,200 capacity) and a “smaller Polaris” (5,000 capacity).

Opened in late 2001, the venue provided a middle tier between Columbus’ clubs and theaters and its arenas, establishing the market as a viable stop for tours of all sizes.

The city’s arenas host multiple sports teams – Ohio State basketball and hockey at the Schott and the NHL’s Blue Jackets at Nationwide – but still find time for plenty of music. About a decade ago, the two arenas united under the CASE banner, joining forces to further increase the market’s appeal at the arena level.

“One of my goals for the last 10 years, maybe longer, is to make Columbus a must-play market,” Gatto said. “We want to be the first play in Ohio, and if there’s only one play in Ohio, the only play in Ohio.”

Gatto cited a sold-out, six-show Garth Brooks run that moved upwards of 90,000 tickets at Schottenstein in 2016 as a career highlight, as well as two-night stands by Taylor Swift (2015) and hometown heroes Twenty One Pilots (2019) at Nationwide.

“It’s pretty special when you get to do multiples in an arena,” Gatto said. “Just people having the confidence in Columbus that we can sell two dates, that we’re with the big boys like Chicago and New York and Dallas.”

CASE also stages shows periodically at the massive Ohio Stadium, including The Rolling Stones in 2015 – “the most iconic rock band and the most iconic college stadium,” in Gatto’s words.

In 2018, AEG acquired a controlling stake in PromoWest, but Columbus isn’t AEG’s town; Schottenstein and Nationwide are both open shops, partnering with Live Nation, AEG, Outback and Feld, and promoting shows independently if the situation calls for it. Rock, country, rap and EDM are the four cornerstone genres in the market, according to Stienecker.

“There’s a lot of rock history in Columbus,” Stienecker said. “It’s a great music city.”

SAN ANTONIO

Steve Zito, general manager of the Alamodome, was at the stadium for eight years after it opened in 1993 before taking a job with the San Antonio Spurs of the NBA, where he was involved in the development of AT&T Center, which opened in 2002. Zito managed the arena its first four years before moving out of the market for 12 years, when he ran Memphis’ FedEx Forum for five years and later spent six years with Andy Frain Services, a crowd management firm. In 2018, he moved back to the Alamodome, where he started a second stint as general manager.

“It’s a very competitive market, I would say we are on the larger side of secondary markets, but we’re also in Texas,” Zito said.

“When it comes to stadium shows, we’re competing with Houston and Dallas and then from the arena side, same thing: Houston, Dallas,” he said. “Austin will enter that market with the new Moody Center. It’s a very competitive landscape here in Texas. Years ago there were more acts than there were venues, and today, it’s almost as if there are more venues than there are acts.”

San Antonio’s long history as a strong concert market dates back to the old HemisFair Arena, the Spurs’ home from 1972-92, “which was a pretty busy venue,” Zito said.

“San Antonio has a great reputation for rock and roll, heavy metal, Tejano and has proven itself to be a strong market for arena acts,” he said. “Obviously the storied history of San Antonio, the culture, the Riverwalk — it’s an awesome city. The people here are so friendly. It’s a walking city. You can go from hotel rooms to the venues, particularly downtown and the Alamodome. Everybody that comes here wants to come back. In some ways it’s a great kept secret and we keep letting the story out one show at a time.”

Those shows take place at a plethora of venues, from the Tobin Center for the Performing Arts to the historic Aztec and Majestic theaters or the Paper Tiger club (formerly White Rabbit), among others.

Promoter Blayne Tucker, owner of San Antonio bar The Mix, said the market has improved over the past 10 years for emerging and independent bands, but “overall there’s still a lot of work to do” to reach its potential in competing against Austin, 80 miles away.

“It’s going to continue to be a challenge as long as (San Antonio) misses a lot of first looks on emerging artists on their first run in Austin,” he said. Austin has one of the highest ticket presale rates in the country, Tucker said, and venues and promoters in Texas’ capital city are able to pay artists more money. San Antonio, by comparison, has a comparatively weak rate of presales.

“There’s a bigger risk, and San Antonio has no Triple A radio stations, whereas Austin has two,” Tucker said.

“So, what happens is an agent that sits in New York or L.A. will get an offer on a show and an agent will look at it and say, ‘But we’re getting $500 in Austin. I don’t see why you’re only offering $250. You’re only 80 miles away.’ In reality, it’s 80 miles away, but they are two different worlds and markets. An agent doesn’t understand that. All they see is just the money in front of them.”

The disparity only grows when acts come through a second time, commanding a higher price.

“Now that band is worth $1,000 in Austin, but they’re still only worth $250 in San Antonio and you don’t ever get to play catch up at that point,” Tucker said.

Tucker would like to see more packaging of emerging acts for tours across Texas.

The Austin-San Antonio disparity “will continue to be a problem until there is a better level of communication between small club owners in both markets, Tucker said.

“There’s some improvement, but with things still under clouds of the delta (coronavirus) variant and all this other stuff, it’s hard to get a good read on how things are going to be going forward.”

Eric Renner Brown contributed to this story.

FIRST RATE: Acts like Metallica, seen here at the Alamodome in San Antonio, make a big splash when they play secondary markets, and they’re more likely to return to venues that treat them well. (Courtesy Alamodome)