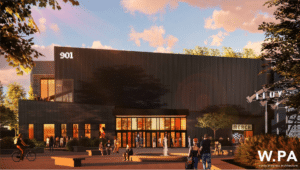

SPIRIT OF 76: A rendering of the proposed Philadelphia 76ers downtown arena, projected to open in 2031. (Courtesy team)

Big winner would be promoters with two Philly arenas

The Philadelphia 76ers made a big splash last week by announcing their intention to build a new downtown arena to open in 2031 and appear to have left the door cracked open for the Philadelphia Flyers to join them.

Multiple sources confirmed that Harris Blitzer Sports Entertainment, the Sixers’ ownership group, met with Comcast Spectacor, their landlord at Wells Fargo Center, the day before the announcement to discuss the project. Those conversations were characterized as more of a briefing than a request to partner in the development, according to one source.

“We aren’t currently partnering with them on this project, but we will continue to explore all opportunities for the best possible outcome for the city of Philadelphia,” said officials with 76erdevcorp, the new company formed by Harris Blitzer to develop the arena.

Comcast Spectacor, a division of broadcast giant Comcast, owns Wells Fargo Center and the NHL Flyers. The company has served as the NBA team’s landlord since the arena opened in 1996 and have invested $350 million in facility upgrades over the past six years. All told, the Sixers have been a second tenant to the Flyers dating to 1967, the year the old Spectrum opened.

Nine years is a long way from now and a lot of things could change over that period of time. Some believe it makes better sense for the Sixers to combine forces with Comcast Spectacor, an industry expert whose core business is managing all aspects of sports and entertainment venues.

In a statement issued the morning of the July 21 announcement, Comcast Spectacor said, “We’ve had a terrific partnership with the Sixers for decades and look forward to hosting the team in this world-class facility until at least 2031. We’ve invested hundreds of millions alongside the city, Phillies and Eagles to make the South Philadelphia Stadium District an incredible destination for sports, entertainment and our passionate fans. We think it rivals any in the nation.”

Regardless, HBSE, whose principals are co-owners Josh Harris and David Blitzer, appear fully committed to 76 Place, the name of the project. The centerpiece is a privately-funded, 18,500-seat arena to be built on a portion of the current site of Fashion District Philadelphia, a mall in the Center City section of Philly.

For HBSE, which also owns the New Jersey Devils, the experience of having Prudential Center as their own arena since acquiring the NHL team in 2013 and controlling all revenue streams has pushed Josh Harris in particular to do the same for the Sixers, with an eye toward future development downtown, sources said.

The site sits less than one mile east of Comcast’s corporate headquarters, and about five miles north of the stadium district, where Wells Fargo Center, Lincoln Financial Field and Citizens Bank Park are situated.

76erdevcorp’s plan is to open the new venue for the 2031-32 season, coinciding with the expiration of their current lease at Wells Fargo Center, local media reported. The site sits on top of a major transit hub, similar to Madison Square Garden in New York and TD Garden in Boston.

“The wave of the future is transit-oriented development,” said David Adelman, a local developer and HBSE’s partner in the project. “We’re literally on top of one of the most active and far-reaching transit stations in Philly that connects to 220 stops.”

The site, the size of one square block, is also close to City Hall and the Reading Terminal Market. There would be some demolition of the existing mall structure to clear space for the new building. The property was originally engineered to support the mall with infrastructure in place to allow for arena construction, Adelman said.

Adelman, a billionaire, is CEO of Campus Apartments, a leading provider of housing for college students. He’s co-founder of FS Investments, a manager of alternative investment funds with $24 billion of assets, and founder of Darco Capital, the name of his family’s investment company.

In addition, he’s lead director of Wheels Up, among the world’s biggest private aviation carriers and a publicly-traded company whose clients include multiple professional athletes, coaches and team owners.

In sports, Adelman has invested in Crystal Palace, an English Premier League soccer team; and the Scranton-Wilkes Barre Railriders, the New York Yankees’ triple-A affiliate. Adelman is a big sports fan and sits courtside at Sixers games alongside the team owners, sources said.

“To do this privately funded, not taking away valuable resources from the city and to do it in a part of the neighborhood where we can help get it to its full potential … I couldn’t be more excited,” Adelman said.

Gensler, part of the design team for Chase Center, the NBA Golden State Warriors’ $1.6 billion arena, will have a prominent role developing 76 Place, Adelman confirmed. General contractor AECOM Hunt, currently building the Intuit Dome, the Los Angeles Clippers’ new arena, is consulting on pre-construction services, he said.

The initial plans for 76 Place extend to retail and restaurant space on the ground floor that will be open year-round, Adelman said.

LIKE A ROCK: Prudential Center, where the HBSE-owned New Jersey Devils are the primary tenant, helped drive the need for a new NBA arena in Philadelphia. (Getty Images)

As part of 76erdevcorp research, Adelman said he’s toured Barclays Center, Fiserv Forum, Little Caesars Arena and renovated Target Center and plans to visit Chase Center. He’s had conversations with the Clippers about their Inglewood, California arena, set to open in 2024.

“The design will be highly sustainable with solar panels and a green roof,” he said. “The other thing that will make it ‘Philadelphia’ is the building will have programming on non-game days to support the (nearby) Chinatown community, with high school basketball and graduations and other events we can put in the arena during the day.”

As it stands now, Philadelphia is the country’s fourth-biggest city for major sports teams by market size with about 3 million homes, behind New York, Los Angeles and Chicago, according to SportsMediaWatch rankings. Unlike the top three, though, Wells Fargo Center, with 20,000 capacity, is Philly’s only indoor venue with more than 12,000 seats.

For 55 years, Flyers ownership has controlled the state of live entertainment in town, dating to sportsbiz pioneer Ed Snider. Building a new downtown facility would create competition against the South Philly arena and dramatically change the dynamic for concerts, family shows and other events.

“The companies that would benefit are (promoters) Live Nation and AEG, because they would have two buildings in Philly to play off each other, so the rent expense would go down,” said Ed Rubinstein. He worked at the Spectrum from 1973 to 1988, including seven years as general manager, and later ran Target Center for two years and Bi-Lo Center, now Bon Secours Wellness Arena.

“That’s the reason why we never wanted another arena built,” Rubinstein, now retired, said. “We had it pretty good at the Spectrum and Wells Fargo Center has it pretty good too. There’s no real competition except for the Camden (New Jersey) amphitheater in the summer. During the rest of the year, there’s only one arena to play.”

Rich Krezwick, a native Philadelphian, served as president of FleetCenter, now TD Garden, for nine years before going on to run Prudential Center for four years, leaving shortly after HBSE acquired the Devils in August 2013. He’s now a consultant after spending the past seven years with AEG. Krezwick, whose facility management career dates to 1978, opened the Boston venue in 1995 and knows about building arenas on top of transit hubs. There are challenges to any urban site with infrastructure and space constraints, and TD Garden went through all of it, he said.

“When Barclays Center opened (in 2012), people said their turntable system for tour production trucks would hurt their ability to have shows,” Krezwick said. “None of that matters when there’s an agent in Los Angeles booking a tour. The urban restrictions can be a problem, but nothing that can’t be overcome and has been overcome in many cities.”

Parking revenue, typically a key income stream for teams, could be limited for the Sixers. At this point, a parking structure is not part of the project, but there are 29 garages within a half-mile of the arena site for fans driving to events, team officials said.

“For the sports complex, Ed Snider controlled it for everybody (including the Eagles and Phillies) and now it’s Comcast,” Rubinstein said. “That’s a big chunk of dough that a building in Center City will not have.”

The key question for the Sixers is whether the numbers pencil out to compete for content in the market. They’re willing to take that risk, considering they’ve played the role of second banana over six decades.

“Usually, when a new building comes on board, the content increases because of the good date availability,” Krezwick said. “If there are 40 big concerts in the market, it might go to 50 or 60, which is a good thing, but will the average rent (deal) go down because there are two arenas now? That’s really the big picture calculation that needs to be done. Wells Fargo Center is not going to roll over and go away. They’re going to be competitive.”

Adelman is confident Philadelphia can support two arenas with 18,000 plus seats.

“I don’t look at it as competition,” he said. “Several top 10 markets have two (large) arenas. It depends on the type of event and where the promoter wants to be. There’s enough for everyone.”