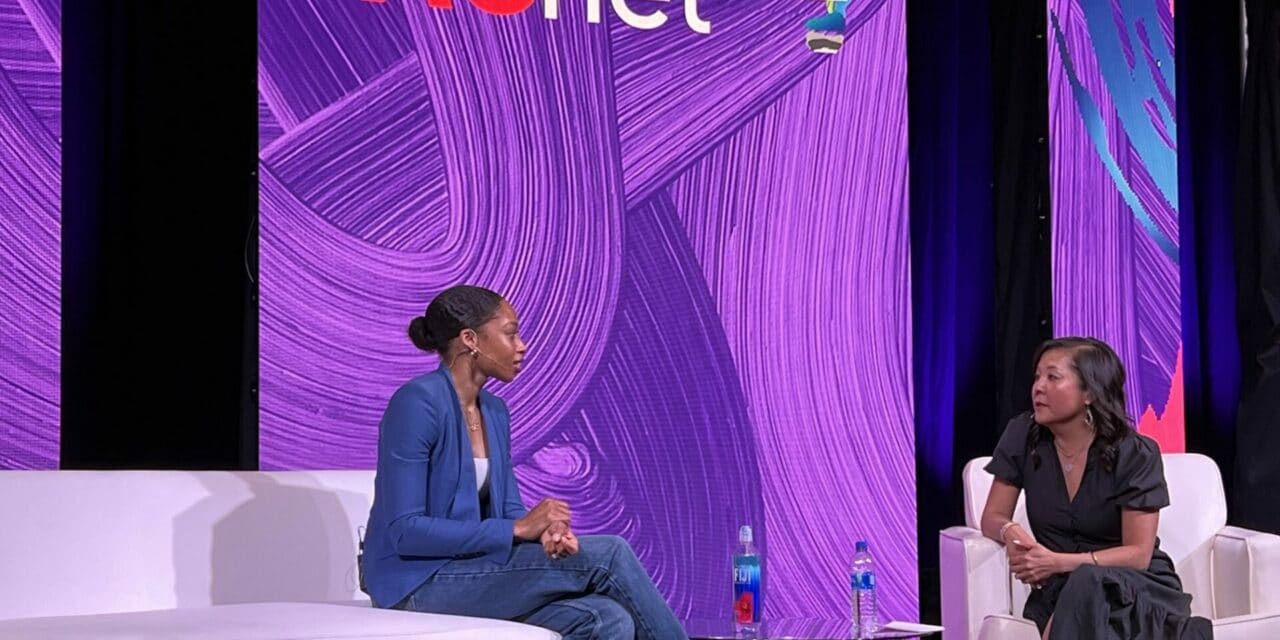

The most decorated Olympic athlete in U.S. history, Allyson Felix sat for a wide-ranging Q&A with Paciolan president and CEO Kim Damron. (Courtesy Paciolan)

Track star, shoe line entrepreneur left her lane in row with Nike

Mother, wife, Olympic track star, female-focused shoe brand entrepreneur, activist — Allyson Felix brought all of her personae to bear in a wide-ranging question-and-answer session at PACnet ’22 on Tuesday.

Before an audience of mostly college/university and performing arts center/theater ticketing, marketing, fundraising and event staff, the most decorated U.S. Olympic athlete shared her take on going pro while a teenager, the controversy over trans athletes, finding time for family and self, carrying on in the face of disappointment and even her philosophy on running a 400-meter sprint.

A topic of particular interest was her battle with former sponsor Nike, a partner of numerous college athletics programs, over how the apparel giant treats athletes and maternity. This was especially notable considering the conflict had much to do with Felix’s own difficult pregnancy.

Under questioning from Paciolan president and fellow USC Trojan Kim Damron (herself clad in kicks from Felix’s Saysh shoe company, a brand co-founded by Felix and brother Wes), the seven-time gold medalist recalled going toe-to-toe with the shoe and apparel behemoth as a “really terrifying experience.”

In 2018, Felix was diagnosed with preeclampsia, which in a worst case can be fatal for mother and baby. She gave birth at 32 weeks to daughter Camryn via emergency C-section and the newborn spent a month in a neonatal intensive care unit.

“The whole situation really just opened my eyes to the maternity mortality crisis that specifically women of color are facing,” she said, explaining that she was already aware of some grim statistics but was shocked and frightened to find herself, an elite athlete, “thrust into that situation.”

“It gave me a heart and passion to do more work in that space and just raise awareness,” she said.

It also led her to pen a New York Times Op-Ed piece taking Nike to task after the company proposed reducing her compensation once she became pregnant.

“When I decided to start a family, I was really scared because in track and field specifically, I had just seen a lot of friends struggle through motherhood,” Felix said.

She had seen women not being supported, or having contacts paused, or athletes hiding pregnancies.

“So, when I was in that same position, where I wasn’t fully supported and I was asking for maternal protections in contracts, I just felt like I had to share my truth and I think being the mother of a daughter, it made it even more clear, because I thought about her and I thought about the world that she’s going to grow up in. I just felt like if I didn’t take this opportunity to speak on this, then it would be left to the next person and to her generation.”

Felix said she was a private person hyper-focused on performance and knew there would be consequences for taking a public stand, “but I just deeply believed that it was the right thing to do.”

In the end, Nike changed its policies regarding sponsored athletes and motherhood and Felix parted ways to later found Saysh prior to her fifth Olympics (in Tokyo in 2021) and become the first athlete sponsored by women’s sportswear brand Athleta, which sells the Saysh line.

Felix also worked with Athleta and the Women’s Sports Foundation to launch a $200,000 grant to help cover childcare costs for competitors.

Earlier in the conversation, Felix talked about the challenge of adjusting to life in college and eventually earning her degree, given she was also an Olympic athlete.

“It was a lot harder than I imagined it would be. I kind of thought it would be like high school. You go to your classes then it’s time for practice and it’s all good,” she said.

But as a pro, the resources available to USC track team members were not available to her and most of her competitions were overseas.

“It took me a little time to adjust and find what worked for me and I made it,” she said, crediting a support system of family, coaches and others who stand behind her still.

Felix said she trains about five hours a day — three on the track, two in the gym.

For many a beacon of confidence and positivity, Felix said that for a year after giving birth she questioned herself. Maybe her best days were behind her. Doubt had also crept in when she lost to the same athlete in the 200-meter sprint in successive Olympics in 2004 and 2008.

But supporters and her own will pulled her through each time.

“Some of my biggest losses and biggest defeats have prepared me for success,” she said. “I used to get so devastated when I would lose a big race. It would almost consume me. Then I understood there is always something to learn from those moments.”

Indeed, she was atop the 200-meter podium in 2012, and in 2021, at the Tokyo Olympics, toddler watching at home, she ran to a 400-meter relay gold and a 400-meter bronze.

Paciolan Chief Financial Officer Kim Boren, left, with Allyson Felix and Paciolan President and CEO Kim Damron. (Courtesy Paciolan)

Fielding a question from the floor on transgender athletes and who they should compete against, Felix called it a complex issue outside her expertise, but added that she is “all for inclusion.”

“I think there is a place for everybody and I want everybody to be involved, but I do think it is very complex and it’s a lot on every level — high school level, collegiate, professional,” she said. “I’m definitely not the one to make any decisions, but I do think we need to be thoughtful with the way that we do things and understand that we’re dealing with people, we’re dealing with young people, and we need to get it right.”

Asked about dealing with pressure, Felix said she logs all of her workouts and every other aspect of her training as it reminds her that she’s prepared.

Sleeping the night before a race is difficult, and she tends to binge watch some TV shows when races are late in the day, as is typical.

At race time, she concentrates on technique, strategy, various scenarios.

“Anybody who’s run a 400 understands,” she said. “It doesn’t matter how fast or how slow you go — it is so painful. It’s not really that much fun. It’s really, really hard. You’re running as fast you can for way too long. I’m typically like, OK, ‘What if this happens in the race or what if I die at 300 meters?’ Playing through all those different scenarios, that’s probably the most stressful.”

Usually once around a standard track, the 400 is highly strategic, Felix explained. Staying true to one’s plan, especially when a competitor goes out fast, takes discipline.

“My strategy has always been, the way that my coach has trained, is you have a pace that you go out and you’re focused on technique and then you have a pace where you come home,” she said. “A lot of it is conditioning and being ready, but I think the challenge of the 400 meters is that it is a strategic race and you can be in the best shape of your life and you can mess it up by not moving at the right time.”