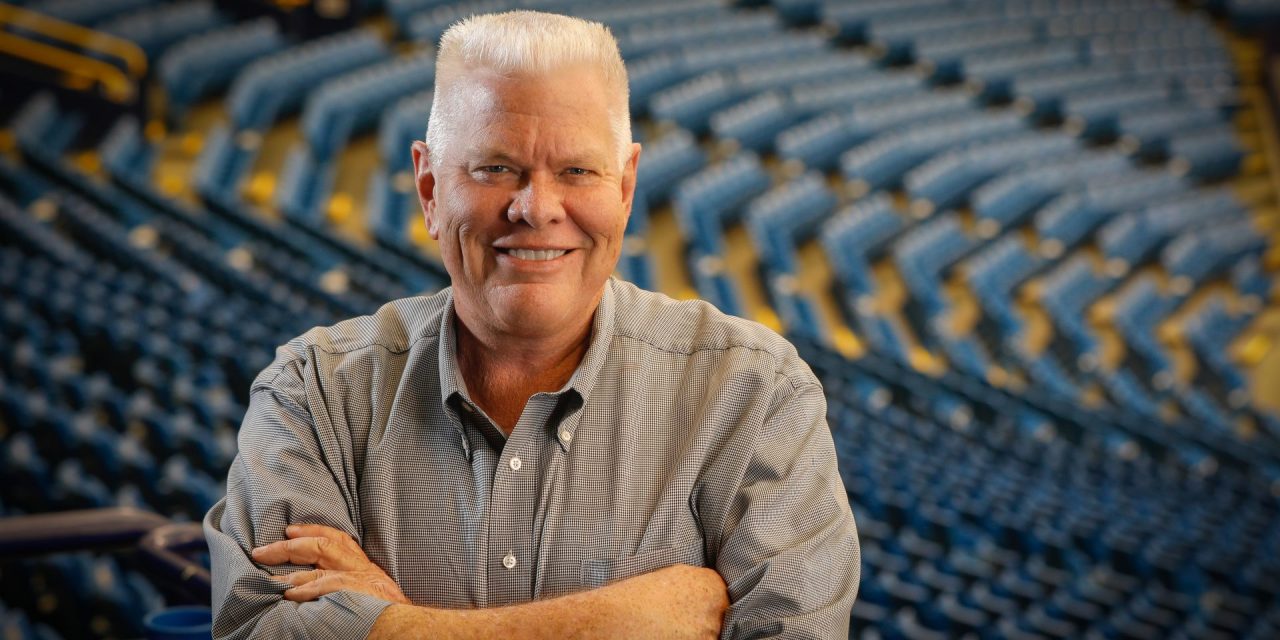

Retired Tampa-St. Pete stadium manager Rick Nafe died on Thursday, according to his wife Dana, who posted a notice on his Facebook page. For about 40 years, Nafe ran multiple venues across Tampa Bay and he was a co-founder and seminar chair of the Stadium Managers Association.

The trade group, which dates to 1974, provides scholarship funds through its foundation for college students pursuing careers in venue management.

To honor his memory, we’re running our story from a few years ago on Rick Nafe’s storied career. In 2019, he was a member of the inaugural VenuesNow Hall of Honor.

HALL OF HONOR 2019: WIT AND WISDOM

CHARISMATIC RICK NAFE TACKLED JUST ABOUT EVERY KIND OF SITUATION IN HIS 40 YEARS OF RUNNING SPORTS VENUES IN TAMPA-ST. PETERSBURG

Posted by Don Muret | Dec 1, 2019 | Arenas & Stadiums, Awards

Rick Nafe typically issues a warning to first-time attendees of the Stadium Managers Association’s annual seminar: Those caught wearing a necktie are in danger of having it cut in two.

It’s a playful threat, but it sends a message to members of the trade group that they can ditch the workplace suit and tie for a more casual atmosphere at SMA.

For Nafe, the association’s longtime chairman, the suits are now permanently stored in his closet. The 67-year-old Miami native retired earlier this year after close to 40 years running sports venues in the Tampa-St. Petersburg area. Twenty-three years were spent running Tropicana Field, the home of Major League Baseball’s Tampa Bay Rays since 1998.

Nafe’s career traces the evolution of Tampa Bay into a big league market with multiple teams and venues. Over the course of his tenure with the Tampa Sports Authority from 1980 to 1996, new facilities were built or in development for the NFL’s Tampa Bay Buccaneers and the NHL’s Tampa Bay Lightning, plus a new spring training facility for the New York Yankees.

In St. Petersburg, Nafe oversaw $70 million in upgrades to Tropicana Field to accommodate the Rays.

Along the way, Nafe worked with some of the most colorful coaches, managers and owners in sports, including George Steinbrenner, John Bassett, Burt Reynolds, John McKay, Steve Spurrier and Joe Maddon. There were also some less colorful folks such as former Bucs head coach Ray Perkins, who never cracked a smile, according to Nafe.

Nafe, known for his keen wit, tried his best to get Perkins to loosen up over the coach’s three-plus years with the Bucs.

“Perkins came from Alabama and the (Bucs) told us he’s a tough person, don’t mess with him,” he said. “His first day in Tampa, they took some publicity shots in the bowl and the Bucs PR guy sent his intern to get a helmet. I had some in my office and sent a (United States Football League) Bandits helmet out there, just to test him to see if he had a sense of humor. He didn’t.”

“We worked OK together,” Nafe said. “I would tease him, saying we’d take him to Tampa General Hospital once a year to have a charisma bypass.”

Nafe’s charisma is on full display at the SMA confabs, where he leads the group from the podium and jabs his brethren with good-natured jokes and barbs. It’s a characteristic that served him well in working with stern personalities such as Perkins and Steinbrenner.

“Underneath that veneer of quick wit beats the heart of a true professional,” said Bill Lester, a colleague who ran the old Metrodome in Minneapolis from 1982 to 2012. “If you play with the big kids, as people in those positions do, you’re going to get knocked around a little bit, but Rick always managed to keep an even keel. He’s the consummate stadium manager, a credit to our industry.”

For those who know Nafe and his natural ability as a public speaker, it’s not surprising that he got his start as a sports anchor for WCTV in Tallahassee, the local CBS affiliate. He started college at the University of Miami before transferring to Florida State and playing football as a walk-on lineman for the Seminoles.

“I practiced football,” Nafe said. “I never got into a game and that was during the infamous 0-11 season (in 1973), pre-Bobby Bowden. I was the worst on a really bad team.”

Nafe graduated from FSU with a degree in mass communications and broadcasting with a minor degree in public relations. He worked in TV for two years before taking a fundraising position with the McDonald Training Center, a Tampa rehabilitation center for the mentally and physically disabled.

In late 1979, Nafe applied for the position of stadium director with the Tampa Sports Authority. Nafe had no experience in venue operations, but he had a love for stadiums dating to his days as a youngster attending events at the old Orange Bowl Stadium, now the site of Marlins Park. There were 250 job applicants, some with facility management experience. After a long two-month process, Nafe was hired to run old Tampa Stadium and a few municipal golf courses.

“I have no explanation on how that happened, and as I tell kids these days, especially interns, there’s no rhyme or reason for me to get that job other than I had a great attitude and a lot of enthusiasm,” he said. “If you have those two things, you can make a lot of things happen, or at least fool a lot of people. One of the two.”

Two years into the job, Tampa was awarded the 1984 Super Bowl. It was a big leap in responsibility for Nafe, who went from “attaching fence ties and pulling weeds” to managing the NFL championship game. In July of that year, Tampa Stadium played host to the USFL title game, drawing a crowd of about 53,000 to see Philadelphia beat Arizona.

At the time, Tampa Stadium had a third sports tenant, the Tampa Bay Rowdies of the old North American Soccer League.

“It was a good start,” Nafe said. “We were busy, and those three years (1984-86) are my favorite years in this business.”

The USFL’s Bandits, playing second fiddle to the Bucs, did their best to drive Nafe crazy through stunts such as bringing a firetruck on the field to spray fans down with water hoses during warm USFL games in late spring and summer, said Jim McVay, president and CEO of the Outback Bowl college football game and the Bandits’ former marketing director.

After the USFL folded, McVay went to work for the Bucs, who struggled during their first 20 seasons in the NFL. As a result, the cannon rolled out to celebrate their touchdowns and field goals wasn’t fired that often. After a while, the pretty girl dressed like a pirate wearing a bikini and poised to light the cannon’s fuse would draw boos after another Bucs mistake prevented a score, shunned by a crowd that thought she might be bad luck.

“Rick had to approve the cannon,” McVay said. “He used to roll his eyes at some of the things we did, but he was understanding and cooperative. Sometimes, these team owners think a little differently … and you better have somebody at the stadium that knows how to put it all together and help you.”

Nafe’s assistance extended to the Twin Cities at a time when the Minnesota Twins were stumping for a new ballpark. Lester, running the Metrodome, brought Henry Savelkoul, chairman of the local sports commission, to Tampa as part of the group’s research for building a new home for the Twins. The dome was also home to football for the NFL’s Minnesota Vikings and the University of Minnesota Golden Gophers.

“We had all three teams in the same building and it was a great public return on investment, but the trend was clearly toward having your own stadium,” Lester said. “The Twins were pushing hard and that was when baseball was having a lot of issues with unequal payrolls. Rick was well connected and he lined up a meeting for us with the mayor of Tampa.”

Nafe knew what they were up against. Tampa officials faced the same issues over the funding of Raymond James Stadium, which opened in 1998, effectively replacing Tampa Stadium. The 65,000-seat building, a $192 million project, was financed entirely with public money after the Bucs fell short on a plan to pay for half of stadium construction in return for 50,000 deposits tied to 10-year commitments for season tickets.

“Rick knew the dynamics of the political and public scene and the decision makers, and that was helpful to us as we gathered information for our own efforts,” Lester said.

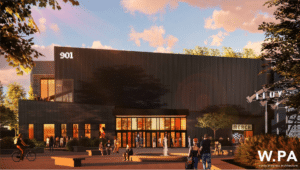

In Tampa Bay, the Rays are in a similar situation. Over the past 15 years, they’ve struggled to find a site for a new ballpark to replace Tropicana Field, which has taken its share of hits over the years over its sterile environment and poor attendance. Nafe hopes the team can work out a deal to build a new stadium, whether it’s in Tampa or St. Petersburg.

“I just don’t believe that Major League Baseball would leave the entire state of Florida to one franchise,” he said. “The Marlins have had their own problems. It’s a tough location to get to. For the Monday through Thursday crowd, it’s hard to leave your office and the city of Miami by 5:30 and make it to Marlins Park in time for the first pitch.”

“There’s no light rail that takes you to the stadium,” Nafe said. “The greatest example and my favorite stadium with all those qualities is Target Field (with multiple transit lines connecting to the Twins’ ballpark). Tampa and St. Pete don’t have light rail, and until that happens, location is going to be a real serious consideration.”

In retirement, Nafe considered driving the water taxi in downtown Tampa, in which he would enjoy narrating the city’s history and local attractions. But after joining a boating club, he had a “little accident” while parking a boat between two vessels and put that idea to rest.

He’s open to consulting after recovering from a recent knee replacement, which followed back surgery in early 2019.

“I would consult if I felt comfortable knowing what I was talking about, whether it was with an architect or a cleaning company,” Nafe said. “Those things are still of interest to me, and I think I’ve learned a lot over the years.”

|READ ON

Lockdown: The birth of enhanced security for the Super Bowl came on Nafe’s watch